“Being male and black in Oakland means being about as likely to be killed as to graduate from high school ready for college. “

—Jill Tucker, San Francisco Chronicle

African American adolescent males are affected by physical and emotional stressors that include “adverse experiences such as racism, poverty, incarceration, and the lack of positive emotional attachments”.[1] These young men are disproportionately impoverished, mis- and uneducated, unemployed and incarcerated. This condition has a moral, societal and economic impact on the nation that manifests itself at the state and local levels. There is a moral issue regarding equity for these young men. It is necessary “to provide opportunities for those who have been excluded because of historical—and current—structural barriers to equality” (Public Health Watch, 2014). As President Obama admonishes, “[g]roups that have [historically] had the odds stacked against them in unique ways…require unique solutions”.[2]

Outcomes for African Americans who live in Oakland or greater Alameda County are consistent with the national data for this population. In Alameda County, one in three African American residents live in a high poverty neighborhood compared to one in fifteen white residents. According to the Alameda County Public Health Department, “African American households have the lowest incomes in the county, at only 51.6% of the income of white households.”[3] African American youth in Alameda County are nearly twice as likely to live in poverty as any other racial or ethnic group in the county. An African American child born in the flatlands of West Oakland has a life expectancy fourteen years less than a white child born in the affluent Oakland hills.[4] Alameda County homicide rates are nearly eight times greater in high poverty neighborhoods compared to affluent neighborhoods.[5] Nearly 86% of all Alameda County homicide victims were males.

Across the board, outcomes for African American adolescent males tend to lag behind other race and ethnic groups. There is pervasive educational underachievement of African American male students in public schools throughout the nation. This is a strong indicator that the system has failed to provide these young men with equal access to a quality education. In 2009, the graduation rate for African American males in the Oakland Unified School District was 49%. During this same period, the graduation rate for white males was 72% and districtwide it was 61% [6].

Among all groups of males in the U.S., African American young men have the worst health outcomes. If they live beyond their adolescent years, adult African American men are between two and five times more likely to be hospitalized for hypertension, diabetes and/or die of heart disease, stroke or cancer. They have a greater risk of suffering from undiagnosed mental illness, such as depression or anxiety. Being subjected to chronic racial aggressions exacerbates these conditions, or may even be a root cause. [7]

The experience of stressful living among African American adolescent males has resulted in a loss of human capital and has a measureable negative effect on the gross domestic product (GDP). Some experts have equated this loss of human capital comparable to a “permanent national recession.”[8] Bringing graduation rates for this group up to the national average for a single year could have earned “an estimated $5.3 billion more in income, generated more than 37,000 jobs and increased GDP by $6.6 billion.”[9]

President Obama and his philanthropic and business colleagues seem to think the time has come to address this important issue. On February 27, 2014, President Obama met with stakeholders at the White House to announce the launch of the My Brother’s Keeper Initiative. The Initiative is a public -private partnership that aims to improve life outcomes for boys and young men of color, up to the age of twenty-five. During his address, President Obama stated that the nation has “become numb to these [dismal] statistics [about boys and men of color and are] not surprised by them.”[10] He further asserts that we take them as the “expected norm [and an] inevitable part of American life, instead of the outrage that it is.”[11]

This paper aims to show how organizations in Alameda County are working to break the cycle of stress and negative outcomes that have plagued this community. These “promising practices” offer hope for dismantling the systemic inequalities that disadvantage African American adolescent males and improving outcomes across the country.

The Cycle of Stress and the Loss of Human Capital

The fact that African American males are not able to fully participate in society is a problem for society as a whole. Many of these young males have dropped out of high school, graduated illiterate, or not pursued higher education. Some lack the necessary skills to participate in the workforce. Some have criminal records that preclude them from employment. These conditions represent a loss of human capital.[12] Rather than being an asset to society (e.g., a contributing tax paying citizen) the non-contributing African American male is a liability (e.g., requires government social services or is incarcerated). Government intervention can serve to mitigate the loss of human capital and have an overall net gain for all Americans and our standing in the global economy.

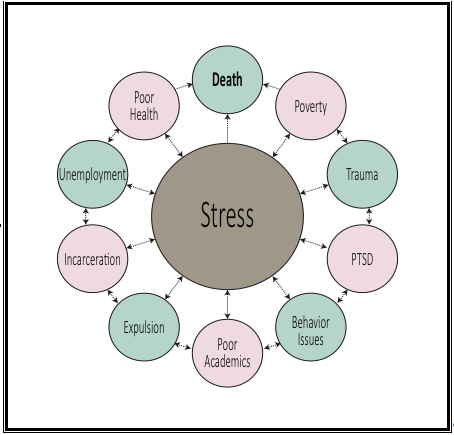

Stressors for African American adolescent males can include adverse factors such as unsafe housing, financial insecurity, violent crimes and unfair treatment. These physical and psychological stressors, which may also include fear of racial discrimination and chronic micro-aggressions, such as racial profiling across socio-economic strata, can trigger stress-related responses such as high blood pressure, higher levels of stress-related hormones (e.g., cortisol) and higher body mass index.[13] Exposure to chronic stressors put young African American men at risk for chronic diseases, such as heart disease and diabetes, and contributes to their morbidity.[14] African American male life expectancy is nearly six years less than white males. The “Cycle of Stress” shows how many of these factors interact with each other. [15]

Figure 1. The Cycle of Stress (after Stokes, 2009)

The cumulative effects of these factors reduce human potential and have a substantial social cost in terms of reduced income and increased public benefits and public safety costs. According to Levin et al. (2007), the public savings attributable to each African American male who graduates from high school would amount to over a quarter of a million dollars. The cumulative effects are large: “simply equating the high school graduation rate of black males with that of white males would yield public savings of $3.98 billion”. [16]

Promising Practices in Alameda County

Although the quality of life for African American adolescent males is rife with physical and emotional stressors, there are results-driven, evidence-based interventions and smart practices that can have a positive impact on what often appears as irredeemable. These promising practices offer competent, gender specific and culturally relevant approaches that build on the strengths of these young men. These practices utilize trauma-informed principles and restorative justice framing so as to “do no harm” and support “healing the hurt” for all involved. This proactive work is delivered without the stigma often associated with delivery of more mainstream therapeutic mental health services.[17]

African American Male Achievement Initiative. AAMA is an initiative of the Oakland Unified School District (OUSD). The Initiative aims to reverse the academic and social inequities facing African American males in Oakland in seven key areas: the achievement gap, graduation rates, literacy, suspensions, attendance, middle school holding power, and juvenile detention. Program staff works within various schools and the district’s operational systems to increase equity, improve cultural competency, and implement practices that support African American male students.

The Initiative includes the Manhood Development Program (MDP) classes specifically for African American males to help them learn how to be successful within the academic environment and larger society. The MDP has successfully created safe spaces in school environments that these same youth have often found to be hostile and uncaring. Youth participating in the MDP have reduced trauma and improved behavior issues as evidenced by an increase in emotional intelligence, critical thinking skills, social acceptance and effective communication skills. Youth expressed a feeling of being more connected to the school.

School-Based Behavioral Health Initiative. This Alameda County Health Care Services Agency Initiative promotes the social-emotional development of all students. The initiative addresses behavioral health-related barriers to learning that are critical to supporting student health and alleviating student stress. It supports the broader mental health needs of the school through prevention initiatives, early intervention group supports, and intensive services for students. These school-based health centers have served to increase access to mental health services among groups, such as African Americans, who are reluctant to seek needed care. More than a third of the populations being served at these centers are African American students. Students utilizing school-based services were reported to show significant improvements in several areas, including anxiety or nervousness, depression or sadness, suicidal ideation or attempt, academic performance, defiant behavior, improved feelings of connection to others, and a sense of empowerment over their future.[18]

Urban Peace Movement. Urban Peace Movement and its partner, United Roots, an Oakland-based media arts center, created a gender-specific healing circle for young African American men called “DeterminNation”. This healing circle works with many African American men who have been involved with street life, gangs or the criminal justice system. These circles, which seem to use trauma-informed practices, provide wellness work void of the stigma that is often associated with more traditional mental health healing practice.[19] A core concept of the program is “street intellectualism.” “Street intellectualism” serves as a foundation to honor the individual cultural strengths and lived experiences of these young men to help them learn to realize their power and self-worth.

Lincoln Child Center (LCC): For over 130 years, the Lincoln Child Center has been working with children, youth and their families impacted by trauma and socioeconomic circumstances to move beyond challenges to become more resilient and successful in life. LCC provides comprehensive mental health services, including school-based services in Alameda and Contra Costa Counties, to vulnerable and emotionally challenged children and families. LCC staff provides a continuum of care to communities with the most needs in an effort to mitigate issues before they become a crisis.

Common Elements

There are some common elements among the aforementioned promising practices that are important to consider when developing a policy recommendation that would effectively support African American adolescent males in reducing stress and trauma in their lives. Fragmented services do not holistically support African American adolescent males to mitigate stress and trauma. It is important that any new policies and interventions include the following elements:

Cultural Relevancy: Acknowledge and address, through program practices, the African American culture. African American males must be engaged in ways that honor how they experience life as an African American.

Gender Relevancy: Practices include socially constructed roles, behaviors and attributes that our society considers appropriate for masculine adolescents. Norms, regarding notions of masculinity, are important to emphasize in the delivery of services to African American adolescent males.

Trauma Informed Approaches: Realization of the prevalence of trauma and how to recognize and respond to it in the delivery of treatment and practices. Program practices must not further harm young African American men seeking support to heal from trauma.

Accessibility: Ease of access to services and programs. School-based programs are the most accessible programs for school age youth. Accessibility can help to mitigate barriers to utilization of stress reduction practices among this population.

Affordability: Provide services that are free or low cost to program participants. Often, these young men have limited resources. Therefore, it is imperative that services be delivered free or at very modest cost to them.

Capacity: Ability to serve the targeted African American adolescent males in Alameda County. There is a great need for stress reduction practices and interventions among this population. There must be a sufficient number of qualified service providers available to support these young men.

Expansion through Research: Build on the evidence-based smart practices and expand the literature review regarding effective practices that support African American adolescent males to reduce stress and trauma in their lives; this includes continuous program evaluation.

The Promising Practices Matrix (Table 1) summarizes the key elements of the programs reviewed above. The policy recommendations cited are the key elements necessary to provide a more comprehensive approach to reducing stress and trauma among African American adolescent males living in Alameda County. While all of the promising practices address several of these criteria, none as yet attain them all.

Table 1. Promising Practices Matrix

Paths Forward

When taken together, these recommendations outline a strategy to support these young men to make sustainable progress toward optimum well-being and full participation in society and the economy. The path forward will require a long-term commitment from Alameda County stakeholders (i.e., local school districts, county behavioral health services, local nonprofits and the philanthropic community) to support African American adolescent males to improve their odds for well-being and success.

As these young men become healthy, active members of society, they positively impact their communities for generations to come. It is in our economic interest to strategically invest in nonprofit and government interventions and evidence-based strategies that are proven to increase life chances and decrease the experience of stressors for disadvantaged African American adolescent males.

About the Author

Sharon Robinson, MPP

Sharon Robinson graduated from the Mills Public Policy program in 2015. Her area of focus is education equity. As an Education Pioneer Fellows, Sharon currently works at the Oakland Public Education Fund as a project manager.

Footnotes

[1] Drexel University (2010). Healthy Communities Matter: The Importance of Place to the Health of Boys of Color. Retrieved from http://www.calendow.org/uploadedfiles/publications/bmoc/the%20california%20endowment%20-%20healthy%20communities%20matter%20-%20report.pdf

[2] White House (2014). My Brother’s Keeper: Creating Opportunity for Boys and Young Men of Color. Retrieved from http://www.whitehouse.gov/my-brothers-keeper

[3] Alameda County Public Health Department (ACPHD) (2014). Alameda County Health Data Profile, 2014, Community Health Status Assessment for Public Health Accreditation. Retrieved from http://www.acphd.org/media/350936/cha_data.pdf

[4] Alameda County Public Health Department (ACPHD) (2013). How Place, Racism and Poverty Matters for Health in Alameda County [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from www.acphd.org/social-and-health…/place-matters.aspx

[5] Alameda County Public Health Department (ACPHD) (2014). Alameda County Health Data Profile, 2014.

[6] Oakland Unified School District (OUSD) (2011). Task Force Summary Report, African American Male Achievement. Retrieved from http://thrivingstudents.org/sites/default/files/AAMASUMReport.pdf

[7] ACDPH, Alameda County Health Data Profile, 2014; ACDPH, Youth Health & Wellness, 2006; OUSD, Task Force Summary Report, 2011.

[8] Oakland Unified School District (OUSD) (2011). Task Force Summary Report, African American Male Achievement. Retrieved from http://thrivingstudents.org/sites/default/files/AAMASUMReport.pdf

[9] Civic Enterprises (2013). Building a Grad Nation. American Graduate. Retrieved from http://www.americangraduate.org/about/about-the-initiative.html

[10] White House (2014). My Brother’s Keeper: Creating Opportunity for Boys and Young Men of Color. Retrieved from http://www.whitehouse.gov/my-brothers-keeper

[11] Ibid.

[12] Gruber, Dr. Jonathan (2011). Public Finance and Public Policy. New York: Worth Publishers.

[13] Public Health Watch (PHW) (2014). Why Racism is a Public Health Issue. Retrieved from http://publichealthwatch.wordpress.com/?s=why+racism+is+a+public+health+issue

[14] Ibid.

[15] Drexel University. Healing the Hurt: Trauma-Informed Approaches to the Health of Boys and Young Men of Color, 2009.

[16] Levin, Henry M., Belfield, Clive, Muennig, Peter & Rouse. Cecilia (2007). The public returns to public educational investments in African-American males. ScienceDirect. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0272775707000829#

[17] Lahound, Jeremy (2013). What Works: Transforming Conditions and Health Outcomes for Boys and Men of Color, California’s Best Practices and Lessons Learned. Movement Strategy Center. Retrieved from http://movementbuilding.movementstrategy.org/media/docs/7717_WhatWorks-BMoCBestPracticesToolkit.pdf

[18] Alameda County Health Care Services Agency (ACHCSA), Center for Healthy Schools and Communities (2014). Annual Conference for Achieving Equity through Community Schools. [PowerPoint Slides].

[19] Lahound, Jeremy (2013). What Works: Transforming Conditions and Health Outcomes for Boys and Men of Color, California’s Best Practices and Lessons Learned. Movement Strategy Center.